2036 Olympics and Paralympics: India formally submits Letter of Intent to IOC

There has been no official confirmation yet but according to reliable sources, the letter was submitted on October 1 with Ahmedabad as the likely host city.

Poor and developing countries need to use their natural resources even if at unsustainable levels, because these are the only resources available for their sustenance. Many estimates have pointed out that nearly half of the worlds population ekes out a living from degraded resources like land and forests. In the future, these resources might not be able to sustain productive livelihoods. But there is no alternative

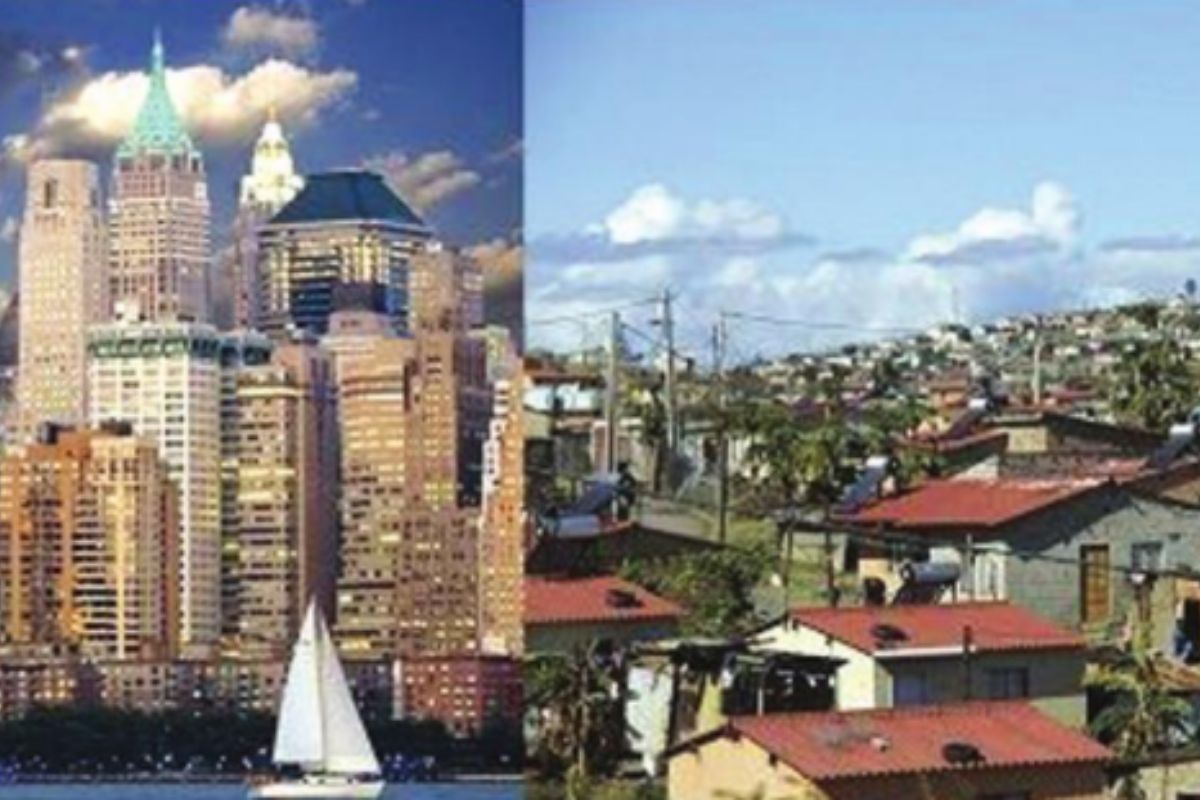

India is progressing economically. But due to this progress, the number of billionaires in the country has risen from only nine in 2000 to 101 in 2017 and to 140 in 2021. In effect, inequality grows when private individual finance framework grows strongest and wealthier than the state system. This has indeed happened in India. Interestingly, a report of Oxfam shows that a daily wage labourer working at the current minimum wage will take as many as 941 years to earn equivalent to the annual income of a Chief Executive Officer of an industrial organization. Another battle of inequality is fuming in the use of natural resources or capital like forests, lands and water. This battle is also related to the consumption that is at the centre of the climate change debate. Like in the climate change debate, in this case as well there is a sharp division between the developed and the developing and the poor countries. While the developed countries are obsessive consumers of natural resources and pump non-comparable level of greenhouse gases (GHGs) into the atmosphere, the developing and the poor countries are just consuming natural resources for survival. The World Bank in its report entitled ‘The Changing Wealth of Nations 2021’ is unequivocally clear on one aspect: wealth is increasing in the world but will not be sustainable in countries that have degraded their natural environment or capital. These countries are the ones who depend more on natural resources for income and sustenance, which dominantly are the poor and developing countries. This is a cause of concern. The report says: “Because low-income countries have so few other assets, proportionately, renewable natural assets such as ecosystems are crucial for them, comprising around 23 per cent of other total wealth.” This is the highest fraction of total wealth coming from renewable natural capital among all income groups. Like GHGs emissions, poor and developing countries need to use their natural resources even if at ‘unsustainable’ levels, because these are the only resources available for their sustenance. Many estimates have pointed out that nearly half of the world’s population ekes out a living from degraded resources like land and forests. In the future, these resources might not be able to sustain productive livelihoods. But there is no alternative. The report also mentions that wealth per capita has grown in low-and middleincome countries due to an increase in agricultural areas and also in harvesting resources like fisheries. But this gain is also at the cost of natural resources. However, the central point is that where the ecology is the main economy, prosperity cannot be assured without the use of natural resources. So the poor and developing countries, or those whose survival and prosperity critically depend on natural resources, will be again put under pressure to bring down consumption. Like in the case of GHGs emission, consumption of natural resources is very unequal. A citizen of a rich country consumes oil and other resources up to 30 times more than those of poor countries. But despite excess consumption, rich countries have reported high levels of natural wealth because their basic survival does not depend on natural resources as much as in poor countries. It is the time for another equity battle, over access and use of natural resources. It is widely agreed that economic prosperity alone will not achieve social progress. High levels of inequality risk leaving much human potential unrealized, damage social cohesion, hinder economic activity and undermine democratic participation. Leaving no one behind is thus a crucial part of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDG 10 calls for progressively reducing not only income inequalities but also inequalities of outcome by ensuring access to equal opportunities and promoting social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, religion or status within society. Social inequalities and educational inequalities go hand in hand. While education is seen as a great equalizer, inequality in access or quality education risks reinforcing social and economic inequalities. The essential economic role of education implies that unequal education can be a driver of unequal outcomes between different groups in society. What is more, educational inequality is at the root of low social mobility across generations. If only the children of wealthy and successful parents have access to the best educational opportunities, inequalities will be more persistent across generations compared to a society where education is less dependent on family background. Understanding of nature and determinants of educational inequality are therefore crucial to the study of overall economic opportunity in a society. Inequalities are humanmade and can be eradicated only through human initiatives. In many ways they are related to individual endeavors as well as moves taken by society and governments. The countries where governments necessarily spend more on education, health, labour welfare and social services, have better attributes to equality. Development Finance International and Oxfam have conducted studies on determining ranking of countries on equality. They inform that Norway, Denmark and Germany are relatively best endowed with equality across the parameters of gender, economics, labour, public service and taxation system. In the words of Professor Himanshu of Jawaharlal Nehru University: “What is particularly worrying in India’s case is that economic inequality is being added to a society that is already fractured along the lines of caste, religion and gender”. It is not that earlier policy-makers were not conscious of the horrific effects of inequality. On 25 February 1956, Jawaharlal Nehru had said, “Democracy has been spoken of chiefly in the past as political democracy, roughly represented by every person having a vote. In the past, a democracy was understood as political democracy, where one person has one vote and one value. But a vote by itself does not represent very much to a person who is down and out, to a person, let us say, who is starving or hungry. Political democracy by itself is not enough except that it may be used to obtain gradually increasing measure of economic democracy, equality and the spread of good things of life to others and removable of gross inequality.” B R Ambedkar had also expressed similar views, stating: “On the social plane, we have in India a society based on the principle of graded inequality, where we have a society in which there are some who have immense wealth as against many who live in abject poverty. In politics we will be recognizing the principle of one value. We must remove this contradiction.” On the eve of departure of the British, on 14 August, 1947 Jawaharlal Nehru reminded the country that the task ahead included “the ending of poverty and ignorance and disease and inequality of opportunity.” There is also constitutional affirmation. Article 38 (2) of the Indian Constitution says: “The state shall, in particular, strive to minimize the inequalities in income, and endeavor to eliminate inequalities in status, facilities and opportunities, not only among individuals but also amongst groups of people residing in different areas or engaged in different vocations.” However, in today’s India most of the policies do not carry the motto of inequality reduction, nor do any political strategies. We should avoid the politics of communalism, hate and monopolisation of wealth and power in the name of development. Because the philosophy of equity never fits into such politics. We should never forget what Amartya Sen said: “I believe that virtually all the problems in the world come from inequality of one kind or another. The success of a society is to be evaluated primarily by the freedoms that members of the society enjoy.”

(Concluded)

The writer is a retired IAS officer

Advertisement

Advertisement